6 Painting Techniques That Don’t Involve a Paintbrush

The youngest of the “big three” Mexican Muralist painters, David Alfaro Siqueiros,

was also one of the first artists to publicly shun the paintbrush,

calling the tool “an implement of hair and wood in an age of steel.”

Seeking new painting techniques fit for the modern age, Siqueiros

established the groundbreaking Experimental Workshop in New York City in

1936. There, young artists like Jackson Pollock gathered to pour, airbrush, scrape, and splatter pigments, incorporating industrial techniques into their artistic practices.

Long after the workshop, artists such as Helen Frankenthaler and Yves Klein continued to experiment with unconventional techniques, expanding the vocabulary of painting to include drips, stains, body prints, and digital drawing, to name just a few. Below, we bring you six painting methods for which artists eschewed the brush in favor of innovative tools and techniques.

Long after the workshop, artists such as Helen Frankenthaler and Yves Klein continued to experiment with unconventional techniques, expanding the vocabulary of painting to include drips, stains, body prints, and digital drawing, to name just a few. Below, we bring you six painting methods for which artists eschewed the brush in favor of innovative tools and techniques.

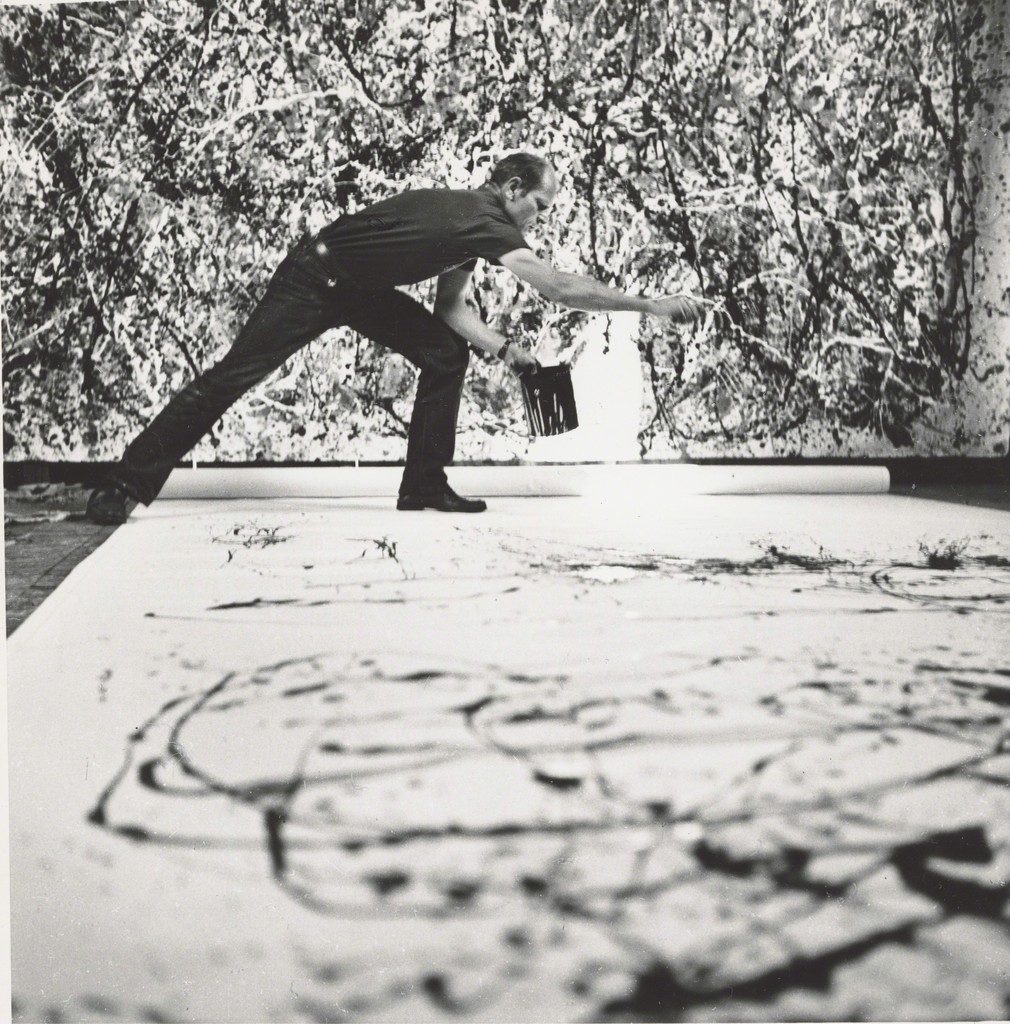

Splattering and Dripping

Enter Slideshow

In February of 1956—exactly 20 years after the Experimental Workshop—Time magazine

nicknamed Pollock “Jack the Dripper.” But while the artist may be most

famous for flinging pigments across canvases, he was hardly the first to

do so. Japanese Zen Buddhist painters, for example, experimented with

splashed ink as far back as the 15th century, long before Pollock

created his first action painting in the mid-1940s.

Pollock’s splatter and drip technique, with its explosive results, captured the curiosity of the American public, especially after the photographer and filmmaker Hans Namuth published footage of the artist at work in his Long Island studio. Placing canvases on the floor, Pollock would incorporate metal rods, kitchen tools, towels, and sticks into his painting process, though these tools rarely touched the canvas directly. “It doesn’t make much difference how the paint is put on as long as something has been said,” the artist once explained. “Technique is just a means of arriving at a statement.”

Pollock’s splatter and drip technique, with its explosive results, captured the curiosity of the American public, especially after the photographer and filmmaker Hans Namuth published footage of the artist at work in his Long Island studio. Placing canvases on the floor, Pollock would incorporate metal rods, kitchen tools, towels, and sticks into his painting process, though these tools rarely touched the canvas directly. “It doesn’t make much difference how the paint is put on as long as something has been said,” the artist once explained. “Technique is just a means of arriving at a statement.”

Pouring

Enter Slideshow

At

the Experimental Workshop, Siqueiros also pioneered a method of pouring

paint directly onto the canvas. His technique of “accidental painting”

involved spilling different colors on top of one another so that the

paint would coalesce into unexpected, swirling patterns on the picture’s

surface. This effect inspired the art historian Sandra Zetina, along

with physicist Roberto Zenit, to recreate Siqueiros’s painting process

in the lab, publishing her findings just last year in an essay titled “A Hydrodynamic Instability Is Used to Create Aesthetically Appealing Patterns in Painting.”

Frankenthaler pushed this technique one step further in 1952 with her pivotal work Mountains and Sea, for which she applied thin washes of paint to an unprimed canvas. Instead of resting on top of the canvas, the paint in this image stained the canvas—a significant feat in an era when avant-garde artists were fascinated with the flatness of painting. More recently, the British artist Ian Davenport has poured stripes of paint down canvases using syringes, letting the colors mix and pool together towards the bottom of his abstract paintings.

Frankenthaler pushed this technique one step further in 1952 with her pivotal work Mountains and Sea, for which she applied thin washes of paint to an unprimed canvas. Instead of resting on top of the canvas, the paint in this image stained the canvas—a significant feat in an era when avant-garde artists were fascinated with the flatness of painting. More recently, the British artist Ian Davenport has poured stripes of paint down canvases using syringes, letting the colors mix and pool together towards the bottom of his abstract paintings.

Pulling and Scraping

Enter Slideshow

The act of pulling and scraping paint is most associated with the Dutch Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning, who achieved this effect with a palette knife, and the German contemporary painter Gerhard Richter,

who often used a squeegee. “With a brush you have control,” Richter

once explained. “The paint goes on the brush and you make the

mark...With the squeegee you lose control.”

Like Pollock’s action painting, the mystery of Richter’s scraping technique inspired the filmmaker Corinna Belz to take viewers behind the scenes. For her fly-on-the-wall documentary Gerhard Richter Painting (2011), Belz spent three years in Richter’s studio, capturing the artist pulling paint across the canvas in what appear to be physically draining gestures. Richter drags, smears, and scrapes layers of wet paint, leaving tracks of his movements across the surface and then covering them up.

Like Pollock’s action painting, the mystery of Richter’s scraping technique inspired the filmmaker Corinna Belz to take viewers behind the scenes. For her fly-on-the-wall documentary Gerhard Richter Painting (2011), Belz spent three years in Richter’s studio, capturing the artist pulling paint across the canvas in what appear to be physically draining gestures. Richter drags, smears, and scrapes layers of wet paint, leaving tracks of his movements across the surface and then covering them up.

Body Printing

Enter Slideshow

Exposing the artistic process even further, the French artist Yves Klein produced

his “Anthropometry” paintings in front of an audience. First held at

the Galerie Internationale d’Art Contemporain in Paris in 1960, Klein’s

performances (now considered by many to be outrageously sexist) featured

nude female models—who the artist referred to as “human

paintbrushes”—rolling themselves in his patented International Klein Blue paint.

The women then proceeded to create imprints of their bodies on giant

pieces of paper, which were arranged on the walls and floor of the

gallery. Behind them, Klein conducted a 10-piece orchestra, playing the

one-note Monotone Silence Symphony, written by the artist himself. The performance lasted for 20 minutes, followed by 20 minutes of silence.

In the 1960s and ’70s, American artist David Hammons created his own series of body prints, using the technique to comment on the Civil Rights-era race riots in the U.S. and the Vietnam War. Hammons often used his own body as the brush, covering himself with grease or margarine before pressing his form onto a surface. Afterwards, Hammons would sprinkle powdered pigments on top of the support, which would stick to the grease and reveal the image.

In the 1960s and ’70s, American artist David Hammons created his own series of body prints, using the technique to comment on the Civil Rights-era race riots in the U.S. and the Vietnam War. Hammons often used his own body as the brush, covering himself with grease or margarine before pressing his form onto a surface. Afterwards, Hammons would sprinkle powdered pigments on top of the support, which would stick to the grease and reveal the image.

Airbrushing

Enter Slideshow

“To

avoid a painterly brushstroke and surface, I use some pretty devious

means, such as razor blades, electric drills, and airbrushes,” explained

the painter Chuck Close in an Artforum interview

in 1970. Originally a photo-retouching tool, airbrushes use compressed

air to spray paint onto a surface, creating smooth gradations that are

reminiscent of photographs.

Close used this technique to depict his friend and fellow painter Mark Greenwold in his large-scale photorealist portrait Mark (1978-9). For the image, Close employed the four basic colors used in color printing—cyan, magenta, yellow, and black—to recreate the photo-mechanical reproduction process, using the airbrush to carefully control the layering of paint. While Close is perhaps the most famous painter to use this industrial tool, other painters like Betty Tompkins have similarly adopted the airbrush technique.

Close used this technique to depict his friend and fellow painter Mark Greenwold in his large-scale photorealist portrait Mark (1978-9). For the image, Close employed the four basic colors used in color printing—cyan, magenta, yellow, and black—to recreate the photo-mechanical reproduction process, using the airbrush to carefully control the layering of paint. While Close is perhaps the most famous painter to use this industrial tool, other painters like Betty Tompkins have similarly adopted the airbrush technique.

Digital Painting

Enter Slideshow

Pollock, Frankenthaler, Klein, and Close may have created paintings without a paintbrush, but pop artist David Hockney makes paintings without any paint. Using his iPad, a stylus, and the Brushes application, Hockney creates vivid landscapes “painted” outside, or en plein air. “People

from the village come up and tease me: ‘We hear you’ve started drawing

on your telephone,’” Hockney wrote in a catalogue for the de Young Museum. “And I tell them, ‘Well, no, actually, it’s just that occasionally I speak on my sketch pad.’”

The California-based multimedia artist Petra Cortright also creates digitally manipulated paintings on the computer. She layers hundreds of found images using Photoshop, often spending up to 12 hours in front of the screen at a time. Like many artists before her, Cortright has taken steps to reveal these unconventional working methods. Her “painting videos” decompose this process of layering images, and have been exhibited as artworks in their own right.

If Siqueiros sought modern painting techniques for the industrial age, then Hockney and Cortright have updated the medium for the digital era. Removing the canvas, the paint brush, and even the paint itself, artists today continue to invent new methods that expand our traditional ideas about what it takes to make a painting.

—Sarah Gottesman

The California-based multimedia artist Petra Cortright also creates digitally manipulated paintings on the computer. She layers hundreds of found images using Photoshop, often spending up to 12 hours in front of the screen at a time. Like many artists before her, Cortright has taken steps to reveal these unconventional working methods. Her “painting videos” decompose this process of layering images, and have been exhibited as artworks in their own right.

If Siqueiros sought modern painting techniques for the industrial age, then Hockney and Cortright have updated the medium for the digital era. Removing the canvas, the paint brush, and even the paint itself, artists today continue to invent new methods that expand our traditional ideas about what it takes to make a painting.

—Sarah Gottesman

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.